The COVID-19 crisis points to how ill-prepared we are to rapidly respond to pandemics. This blog addresses one facet of this problem: the lack of availability of blood samples from infected and post-infected individuals for use in developing diagnostic tests and treatments.

Very early on in this crisis, companies were scrambling to find blood samples to use in the development of diagnostic tests for COVID-19. The lag in test development and access significantly impaired our ability to initially understand the impact of this pandemic and accurately track its spread. Even now, only a very small percentage of the population is being tested.

As preparations are being made to reopen the economy, there is a need to determine who is or was infected (and possibly immune). This need will remain of critical importance as people return to work and other activities. The CDC and diagnostic companies are seeking blood samples to develop tests for COVID-19 antibodies in blood. Although more studies must be done, the presence of antibodies in a person’s blood is an indication that they may have some immunity to the disease. Antibodies from their blood might also be an effective treatment for critically ill patients until an effective vaccine is developed.

The problem is that the search for blood donors and samples is happening in a piecemeal manner, with very little organizational infrastructure to support it. Companies are placing ads on TV and in newspapers and sending out emails in hopes of finding donors. Likewise, the CDC is contacting companies such as ABS, hoping that they may access samples.

Many of our collection sites are only now ramping up to collect nasal swab and blood samples. This is causing delays at a time when delays are not acceptable. Delays cost lives and further damage the economy during a crisis.

Hospitals that are desperate to treat patients cannot be expected to explain and ask seriously ill patients in emergency rooms or intensive care units for consent to donate a couple of tubes of blood. Furthermore, no system ensures that samples, even if they were collected, would go to the laboratories where they would be most effectively utilized. There should be a better way.

The solution proposed here reduces the time required for acquiring samples from weeks or months to days. The technology to make this possible already exists. For example, a national Wireless Emergency Alert system is in operation. Alternatively, individuals could opt in to download an app that stores opt-in contact information in a secure database in the event of a government declare emergency. Similarly, Apple and Google are partnering to develop and implement a smartphone system that will track COVID-19 infected individuals and alert others if they encounter such individuals.

The Apple / Google system requires users to opt into the system. Users need to notify the system if they are diagnosed with COVID-19. A minor addition to the opt in would enable users to contribute blood samples for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

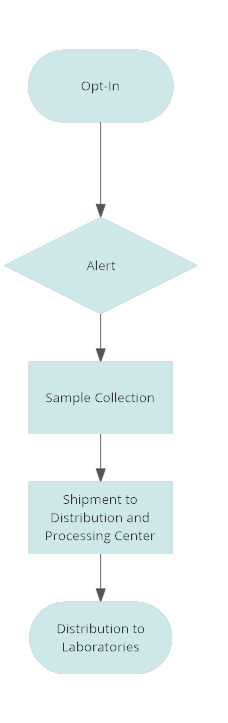

Whether through the Wireless Emergency Alert system, the Apple/Google system, or some other opt-in system or app, infected individuals could be given the opportunity to donate blood for research or therapeutic purposes. Opt-ins would be stored in a secure database run by the federal government or an organization contracted by the government solely for this purpose.

This process could be extremely fast. Ideally, in advance of an epidemic, individuals could opt-in to participate in a network dedicated to providing samples if the need does occur. Once the federal government declares an emergency, all users who have opted in would receive an alert with information on how to respond.

Partnering with a network of blood banks would facilitate sample collections. For example, bloodmobiles that are operational in many locations, could be dispatched to virus hot-spots for collections. Similarly, mobile phlebotomists could be dispatched to donors or hospitals to assist with sample collections. There are organizations that already to sample collections for clinical research trials. These groups could be catalogued, signed on, and rapidly activated in an emergency.

Expenditures would be minimal, especially in comparison to the current situation of trying to catch-up with events. Minimal investment in additional infrastructure is required because the infrastructure already exists. It only needs to be activated for the purposes that are described here.

A central distribution center would dispatch premade collection kits to collection sites or phlebotomists, and these kits would be returned to the center via FedEx or another express carrier. The samples would then be stored or distributed to research groups under the direction of the CDC or some other designed government review group. ABS already has expertise in organizing sample collection and distributions for our pharmaceutical and biotechnology clients, so we know that this type of networked system works without huge expenditures and overhead. Moreover, it would be relatively simple to test its feasibility in a pilot project. Its implementation as part of a pandemic response would save lives and reduce the damage to the economy that we are now experiencing.